The following text is an excerpt from part 1 of a three-part Mahabharata-summary, available as an ebook from Google Play, Atmarama-Shop, Apple and others:

Mahābhārata – Juwel of the Poets

I. The History of the Pandavas – Retelling of the Main Story

1. Prehistory

The first part of this book contains a summary of the main story of the Mahābhārata, culminating in the Battle of Kuru-kṣetra. Sūta Gosvāmī tells the story known as the Mahābhārata to a group of sages who performed a long-standing sacrifice somewhere in the forest of Naimiṣāraṇya. He himself heard the Mahabharata from Vaiśampāyana, a disciple of the Dvaipāyana Vyāsa, in the court of King Janamejaya, the last great ruler of the Kuru dynasty.

»Duryodhana is a large tree of evil passions. Karṇa is its stem, Śakuni its branches, Duḥśasana its flowers and fruits, and Dhṛtarāṣṭra its root.

Yudhiṣṭira is a large tree of righteousness. Arjuna is its trunk, Bhīma its branches, the sons of Madrī its flowers and fruits, and Kṛṣṇa and religion and all the brāhmaṇas are its root.« — Adiparvan, Chap. 1, Verses 65-66

In the forest of Naimiṣāraṇya

Sūta Gosvāmī, the son of the wise Romaharśana, was widely famous for his knowledge of the sacred stories of the world, the Purāṇas. Once he wandered to the holy forest of Naimiṣāraṇya, where the learned Śaunaka performed a twelve-year-long sacrifice with the help of powerful self-controlled sages. Sūta approached the saints sitting in the sacrificial arena, and with his head bowed and his hands folded, he inquired about their welfare and the progress of their renunciations. The ascetics of the forest welcomed him in their midst, eager to hear the captivating stories that the son of Romaharśana knew so well and offered him an elevated seat. When he had taken his seat, they offered him fruits of the forest and a cup of fresh water. Then Śaunaka Ṛṣi said, „O lotus-eyed Sūta, may we know which holy places in Bharata-varṣa you blessed with your presence and which holy persons you met on your journey? Please tell us everything that happened to you.“

The snake sacrifice

Sūta Gosvāmī replied, „O you ṛṣis, recently King Janamejaya, who is a great soul among earthly rulers and the worthiest son of Mahārāja Parikṣit, performed a great snake sacrifice with the intention of destroying all the snakes of the world in the fire. During the sacrificial ceremony, the great Muni Vaiśampāyana narrated many significant stories, all known collectively as the Mahābhārata, which he had heard from his spiritual master, the exalted Dvaipāyana Vyāsa. I was one of the listeners in the assembly. Afterwards, I visited various tīrthas (holy places) and finally came to Samanta-pañcaka, where many qualified brāhmaṇas live. At that place, not long ago, the great battle took place between the Kurus and the Pāṇḍavas and all the kings of the earth. Then I went to Naimiṣāraṇya to see you who are all self-realised souls.“

The sages were very eager to learn from Sūta Gosvāmī about the snake sacrifice and the Mahābhārata, so Śaunaka Ṛṣi, the son of Romaharśana, asked the wise Sūta, „How did this snake sacrifice come about? What was the cause and with what intention did the grandson of Abhimanyu accomplish this sacrifice?“

Sūta Gosvāmī told that King Janamejaya had been encouraged by the Ṛṣi Uttaṅka to make a serpent sacrifice. Uttaṅka wanted to take revenge on a nāga1 named Takṣaka, because he had once been put in bad trouble by Takṣaka. But this is a long story and we do not want to go further into it here. In any case, this much can be said: Uttaṅka's thoughts of revenge were one cause of the snake sacrifice. Another cause was Janamejaya's hatred of snakes, which manifested itself when he learned from Uttaṅka how his father, Mahārāja Parikṣit, had been killed.

Parikṣit had once passed by the āśrama of the sage Śamika during a hunt, tired and thirsty. The sage sat absorbed in meditation in front of his hut and did not move to receive his royal guest properly or at least offer him some water, as is the custom in vedic culture. Angered by the ṛṣis's behaviour, the king hung a dead snake around his neck with the end of his bow and left the place. A little later Śṛṅgi, the sage's son, came home and saw his father sitting on his deer skin with the snake around his neck. Śṛṅgi was still a boy, but he already possessed mystical powers, which one acquires through penances and renunciation. This made it possible for him to see who had inflicted this insult on his father. And because he was still very immature, he became angry and cursed the king for this act of being bitten by the serpent king Takṣaka within seven days. When Śamika had finished his meditation and learnt what Śṛṅgi had done, he was greatly grieved at his son's fatal action. Parikṣit was a good king who ruled the world in accordance with dharma, the divine laws, and to punish such a ruler with death for a minor offence was an unworthy act for a brāhmaṇa. Therefore, the sage instructed his son about the true wealth of the brāhmaṇas, namely forgiveness.

Another reason for the snake sacrifice was a curse that Kadru, the primordial mother of all snakes, had placed on her own children because they had refused to help her in a fraudulent action. In connection with this story of ancient times, Vaiśampāyana told of the birth and glory of the mighty Garuḍa, the king among birds, who serves as Śrī Viṣṇu's carrier, and he told the story of the Brāhmaṇa Astika, who finished the snake sacrifice and thus saved Takṣaka and other snakes from death by fire. In the snake sacrifice, all kinds of snakes — and not only from this planet — were forced by experienced sacrificial priests through mantras to fall into a great sacrificial fire and give up their lives. Takṣaka, however, was lucky. When he was already hovering over the fire, the Brāhmaṇa Astika appeared on the scene and asked the king to grant him a wish. Janamejaya agreed, and Astika wished the king to finish the snake sacrifice.

Śaunaka ṛṣi, the best among the assembled sages of Naimiṣāraṇya, asked Sūta Gosvāmī to narrate the conversation between King Janamejaya and Vaiśampāyana Muni. Sūta Gosvāmī gave a brief summary of the Mahābhārata, the story of the Pāṇḍavas. Because the ṛṣis did not feel completely satisfied, Śaunaka said, „Oh Sūta, we are not satisfied with hearing the Bhārata in an abridged version. Please give a detailed account of all that you have heard. Please narrate this holy and sin-purifying story fully and in detail.“

The birth of Satyavatī

Sūta Gosvāmī then first narrated — not least to pay due respect to the author of the Bhārata — the unusual birth of Satyavatī and the equally unusual birth of her son Vyāsa, whom she gave birth to on an island in the river Yamunā and who therefore got the byname Dvaipāyana („island-born“).

On that day, when the pious King Uparicara, a descendant in the dynasty of Kuru, was about to unite with his young, beautiful wife Girikā to have a good son, his Pitṛs (ancestors) appeared before him and asked him to make an offering for them, with an animal that he should kill in the forest. The king thought to himself, „This is very unpleasant for me, but what can I do? The Pitṛs should be obeyed“. During the hunt he thought only of Girikā, and when, somewhat tired, he sat down under an Aśoka tree, his longing thoughts of the beautiful girl were so strong that he unintentionally emitted semen. He caught it on a leaf of the tree and thought about how this semen could reach Girikā before he had done his work for the Pitṛs. This semen carried the heritage of a great dynasty of highly qualified Kṣatriya kings and was to produce a fruit in his good wife. A falcon was perched on the tree, and since the king was a good falconer and also understood the language of falcons, he ordered him to take this semen to Girikā.

On the way to the queen, however, the bird was attacked above the Yamunā by another falcon, which mistook what Uparicara's falcon carried in its beak for prey. They fought each other in the air and in the process the semen fell into the river. A fish swallowed it. This fish was actually an apsara (celestial society girl) who had been cursed to live as a fish. After nine months it happened that the fish was trapped in the net of some fishermen who were quite astonished when they cut open the animal and out of its belly came two children, a boy and a girl. They took the children to King Uparicara and the king kept the boy and handed the girl to the king of the fishermen because she emitted a strong fishy smell. The king gave her the name Satyavatī.

The birth of Dvaipāyana Vyāsa

When Satyavatī had grown up a little, she took on the task of ferrying people in a boat from one bank of the Yamunā to the other. One day, the young ṛṣi Parāśara was wandering along the Yamunā. He was a highly respected personality among all the saints, and he had been instructed to beget a divine son who would divide the one Veda fourfold so that future generations of human races on earth and on other planets would have easier access to the spiritual science by which one can transcend the bonds of material nature and attain immortality. When he saw the girl, he knew that only she could be the suitable mother for this son. He could also see who her real parents were. Parāśara boarded Satyavatī's boat and while she was rowing, he revealed his mission to her and asked her to conceive a divine son from him.

Satyavatī, concerned for her honour and fearing to be cursed by the ṛṣi if she did not obey his will, replied, „Oh venerable one, I am a virgin and under the protection of my father. Moreover, how can I accept your embraces since those ṛṣis standing there on the other bank of the river can see us?“ Thereupon Parāśara Muni created a thick mist by his mystic power. Still fearing the consequences of uniting with the Muni, Satyavatī said, „What will my father say, and then who will take me as a wife if I obey your will?“

Parāśara replied, „Don't worry, you will be a virgin again!“ He also granted her a blessing and Satyavatī wished to possess a fragrant body. Then he made her row to an island in the Yamunā and begot Vyāsadeva with her. Like the Devas, Vyāsa was born shortly after conception and grew to youthful stature within a few moments. Immediately he set his heart on the practice of tapasya (austerities) and left his mother. As he walked, he told her to think of him when she needed his help; he would be there immediately. At a sacred place in the Himalayas, he underwent austerities and renunciation for a long time and compiled the Vedas and the Mahābhārata as the fifth Veda.

The sons of Diti and Aditi

Next, Sūta Gosvāmī related what he had heard of the birth of the great heroes in the Mahābhārata of Vaiśampāyana. He told of Paraśurāma, the warrior incarnation of Viṣṇu, and then of the time when the Daityas (demon race; sons of Diti) had been driven from the heavenly planets by the Ādityās (demigods; sons of Aditi) and had incarnated on earth.

Sūta Gosvāmī told of the sons of the four-headed Brahmā born from Viṣṇu's navel and how the universe had been filled with living beings. When, after a dissolution of the material worlds, the universes arise anew by the will of the Supreme, the Supreme Lord enters each universe in His Viṣṇu form. Each universe is half filled with water and on this ocean Viṣṇu lies down. He then sprouts a golden lotus from his navel and from the flower is born Brahmā, who then, empowered by Viṣṇu, carries out further creation, creates the planets, etc., and populates the universe with living beings. Śrī Viṣṇu reveals the Vedic knowledge to Brahmā in his heart and the grandfather of the universe then instructs his sons in it, who in turn pass it on to their sons and disciples. In this way, the Vedas are given to living beings from the very beginning of creation for their benefit.

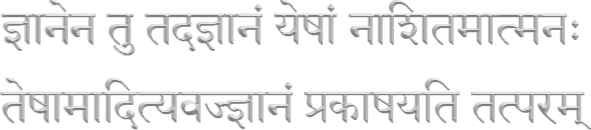

The Vedas are a kind of divine code that sets the guidelines for civilised human life and guarantees happy living conditions for their followers. Ultimately, however, the Vedas aim to give the eternal living beings knowledge through which ignorance is destroyed and through which they can be liberated from the cycle of birth and death. Due to the enchanting power of material nature (māyā), eternal living beings identify themselves with their respective temporary bodies. They forget their true spiritual nature and instead, under the spell of māyās, try to exploit the riches of the material world. Because of this tendency, living beings suffer the torments of birth, old age, disease and death again and again. The Vedas are an expression of the Supreme Lord's mercy because through their spiritual teachings the conditioned souls can be liberated from this unnatural state of perpetual rebirth.

Those who follow the instructions of the Vedas and acknowledge the supremacy of Viṣṇu are called suras or Devas, demigods or devotees, and those who disregard these instructions and act according to their own whims and fabricate their own gods and laws are called asuras or demons. A demigod may well temporarily fall into the mentality of a demon, while a demon may also become a devotee through communion with pure devotees.

Brahmā created the first living beings from his mind. One of his first sons was Marici. Marici had a son named Kaśyapa. Kaśyapa married Diti and Aditi. Aditi gave birth to twelve sons called the ādityās, which included Sūrya, the sun god, and Indra, the king of heaven. The ādityās and their descendants are demigods, while the daityas, the sons of Diti, and the descendants of the daityas are usually atheistic demons. However, there are exceptions. The demons populated the lower planetary systems and the demigods the higher planets. Sometimes the asuras go to war against the Devas, and sometimes they succeed in conquering the celestial kingdom and driving out the Devas. The last victory over the demigods was achieved by the daityas under the leadership of Bali Mahārāja. Bali, however, was deprived of his dominion over the three worlds (higher, middle and lower planetary systems) by a trick of Viṣṇu (Śrī Vāmanadeva) so that Indra could resume his post as king of heaven.

Devas and Asuras incarnate on Earth

After Bali's fall, the Asuras fled and — incarnating in large numbers among humans and animals — sought refuge on Earth, making it their base for a new attack against the Devas. Over time, the Asuras became an unbearable burden for Mother Earth, so she went to Brahmā in the form of a cow and, with tears in her eyes, asked him for help. Brahmā could not help Mother Earth directly, but he approached Śrī Viṣṇu, and the deity promised to appear in due course in the Vṛṣṇi dynasty and relieve the Earth of her burden. Thus the Supreme Lord, Kṛṣṇa, took birth in His original form in Mathurā as the son of Devakī and Vasudeva to protect the pious from the godless Asuras, to kill the Asuras and to re-enunciate the forgotten principles of true religion. The Lord performed his childhood pastimes in the cowherd village of Vṛṅḍāvana2 and later had the city of Dvārakā built, where he married 16108 queens, expanded into as many forms and lived with each queen in a grand palace. In Dvārakā, Kṛṣṇa played the role of a perfect Kṣatriya king. At the time of His appearance, many Devas also incarnated to participate in the līlā, the transcendental pastimes of the Lord.

Vaiśampāyana then narrated as which persons the great Devas and daityas had incarnated on earth. To give a few examples: Droṇa was a partial extension of Bṛhaspati, the guru of the demigods; Aśvatthāmā was a partial extension of Yama, Kāma, Krodha and Mahādeva. Kṛpa was a partial expansion of the Rudras (eleven expansions of Lord Śiva); Śakuni was Dvāpara (Lord of the dvāpara-yuga); Sātyaki was a partial expansion of the Maruts, also Drupada, Kṛtavarman and Virāṭa. Duryodhana was Kali (lord of the kali-yuga), and Duryodhana's brothers were sons of Pulastya. Varcas, the son of Soma (demigod of the moon), became Abhimanyu, the son of Arjuna. Dhṛṣṭadyumna, born of fire, was a partial extension of Agni (demigod of fire). Pradyumna, one of Kṛṣṇa's sons, was the famous celestial ṛṣi Sanat-kumāra. Draupadī was an extension of Lakṣmī (the goddess of fortune) and Sacī (consort of Indra). The Dānava Vipracitti incarnated as Jarāsandha and Ajaka, the younger brother of Vṛṣaparvan, as Śālva. Ekacakra had taken birth as Prativindhya, son of Yudhiṣṭira, Saṃhrāda, the younger brother of Prahrāda, as Śalya, and Anuhrāda as Dhṛṣṭaketu. The asura Bāṣkala became the mighty Bhagadatta, who was an ally of Duryodhana in the great battle and, riding on a giant white elephant, decimated the ranks of the Kurus. Kaṃsa and Śiśupāla, who were both killed by Kṛṣṇa before the battle of Kurukṣetra and thus gained liberation, were the Dānavas Kalanemi and Hiraṇyakaśipu.3

The dynasty of the Kurus

Vaiśampāyana then spoke of the dynasty of the Kurus, beginning with the great ruler Yayāti. Yayāti lived a long time ago, when people became much older than today. He was the son of the powerful world ruler Nahuśa. Nahuśa even held the position of Indra for a long time, until he lost this position again due to his arrogance, pride and offences against brāhmaṇas. There are only seven generations between Brahmā and Nahuśa. However, one must bear in mind that each generation lasted for millions of years. Yayāti had five sons. When this ruler was overcome by frailty due to a curse of Śukrācārya, he asked his sons one by one to give him their youth in exchange for his decrepitude, as his desire for worldly pleasures was not yet satiated.

But only Puru, Yayāti's youngest son, agreed to sacrifice his youth. And when Yayāti realised after a thousand years that there is no end to desires, i.e. that the hunger for sensual pleasure can never be satisfied by trying to satisfy it, he returned his youth to his youngest son and said to him: „O conqueror of your enemies, with your youth I have enjoyed the pleasures of life to the full measure of my desires, to the limits of my strength. Desires, however, are never satisfied by corresponding actions. On the contrary, when steps are taken to satisfy desires, they only blaze up more, like a sacrificial fire on which butterfat is poured. If a man possessed everything on earth — their cornfields, their gold and silver and precious stones, their animals and women — he would still not be satisfied. Thirst for enjoyment should therefore be abandoned.“ Then Yayāti went into the forest to take upon himself penances and renunciations. Puru became heir to the throne. Normally, in Vedic civilisation, the eldest son of a king became his successor. Several generations later, Duṣyanta was born in this dynasty. Duṣyanta begat with Śakuntalā Mahārāja Bharata.4

A few generations after Bharata, the powerful virtuous emperor Samvarana was born, who took Tapati, a daughter of the sun-god Vivasvān, as his wife and begat Kuru with her, after whom was named the dynasty in which the Pāṇḍavas (sons of King Pāṇḍu) and Dhārtarāṣṭras (sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra) appeared. Kuru had four sons. In the line of his son Jahnu, Pratipa appeared ten generations later and his successor was Śāntanu.

Śāntanu marries Gaṅgā and begets eight sons with her

One day, Mahārāja Śāntanu met the goddess Gaṅgā in the forest, and charmed by her beauty, he proposed marriage to her. Gaṅgā agreed to become his wife on the condition that Śāntanu should never say an evil word against her, whatever she does, and that he should never ask the reason for her actions. Mahārāja Śāntanu begot eight sons with Gaṅgā, each of whom — except the last — she threw into the Ganges immediately after birth, saying, „I do what you wanted“. Śāntanu was very depressed every time his wife threw a newborn into the river, and when she also wanted to throw the eighth child into the Ganges, he could restrain himself no longer and rebuked the goddess with harsh words, whereupon she said that her time with him was now over according to their agreement. Gaṅgā revealed her true identity to the king and told him that the slain children were the demigods called Vasus, who had been cursed by the great ṛṣi Vasiṣṭha to be born on earth, and who had chosen her as mother and him as father, and that it was the will of the Vasus to be thrown into the Ganges immediately after birth.

The Vasus steal Vasiṣṭhas Kāmadhenu cow

Śāntanu Mahārāja wanted to know more about this and Gaṅgā told the following story: „Once the eight Vasus were wandering with their wives through a charming forest on the edge of Mount Meru. In this forest was also the āśrama (refuge, cottage) of Vasiṣṭha Muni, who was a son of Varuṇa, the demigod of waters. He practised austerities and renunciation there to attain purity of soul. When the Vasus passed by this āśrama, they saw the beautiful Kāmadhenu, a wish-fulfilling cow of the sage. She was a daughter of Kaśyapa Muni and Surabhī, the famous daughter of Dakṣa. The cow provided Vasiṣṭha Muni with everything he needed for his sacrificial rites. Dyu, one of the Vasus, extolled the extraordinary abilities of the kāmadhenu and particularly emphasised that her milk was nectar that granted the drinker a long life, free from disease and infirmity. Dyu's wife was very enchanted by the miraculous cow. And since its owner was not at home at that time, she asked her husband with skilful flattering words to simply take the kāmadhenu with them. Dyu's wife had a friend among the humans, who was the daughter of the great king Uśinara. To her she wanted to give the cow, so that the king's daughter would drink the milk and become as long-lived as the celestials, like herself. Dyu was persuaded by his wife and stole Vasiṣṭha's beautiful kāmadhenu. When the sage came home, he missed his miracle cow. And though Vasiṣṭha looked for her all over the forest, he did not find her. Then, through his spiritual eye, he realised what had happened and in anger cursed the Vasus to take birth on earth.

In the meantime, the Vasus had reached their house and soon realised that a curse was upon them. So they went to Vasiṣṭha's āśrama and brought him back his kāmadhenu. They paid their respects to him and begged him to remove the curse from them. The Muni said, ‘I cannot repeal this curse, for my words can never prove untrue.’ However, having pity on the Vasus, he assured them that all but Dyu would return to the heavenly regions within a year. Dyu was to live a long time on earth and he was to be considered — good fortune in misfortune — a highly respected person who would be familiar with all the scriptures and devoted to dharma. He would also remain celibate for his father's sake. On their way back, the Vasus met me, Gaṅgā, and told me of their misfortune. They requested me to appear on earth as their mother and to throw them all into the Ganges immediately after birth, so that they could return to the celestial region at once.“ After speaking these words, the goddess left Śāntanu along with the newborn boy, whom she named Devavrata.5

Devavrata studied the Vedas with Vasiṣṭha Muni. After a few years, when Devavrata had become proficient in all branches of Vedic knowledge and a great warrior, his mother brought him back to Śāntanu.

Devavrata's oath

Some time later, the king married Satyavatī, Śrīla Vyāsadeva's mother. When Śāntanu asked the Niśada king for her hand in marriage, the king made it a condition that Satyavatī's sons should become heirs to the throne. The ruler of the earth did not accept the condition, as Devavrata was rightfully his successor, and went back home grieved. To help his father, Devavrata went to the Niśada king and took an oath before him to renounce his right to the throne as Śāntanu's eldest son and never to enter the gṛhastha-āśrama (householders' state of life). I.e., in other words, he would not be able to have any sons who might contest the throne with Satyavatī's son. At his oath, the demigods rained flowers and shouted delightedly, „Bhīṣma, Bhīṣma shall he be called!“ Bhīṣma means „one who has taken a terrible oath“. Śāntanu, in gratitude, gave Bhīṣma the blessing of being able to determine his own death.

Citrāṅgada and Vicitravīrya

Satyavatī bore the emperor two sons, Vicitravīrya and Citrāṅgada. When his two sons were grown up, Mahārāja Śāntanu, after ruling the world for thirtysix years, took vānaprastha; he retired to the forest to undergo penances and renunciations for the rest of his life and to prepare for the next life. Śāntanu was an ideal king, a saint among rulers. During his reign, the people led a happy healthy existence. Like their exalted king, their great inspiration, their thoughts and aspirations were directed towards the one great goal of satisfying and worshipping the cosmic Sustainer, Śrī Viṣṇu, and they fulfilled their respective duties in the varnas and āśramas with joy. The brāhmaṇas guided the kings on the path of dharma and taught Vedic knowledge; the kṣatriyas obeyed the brāhmaṇas and protected the citizens, including animals, birds and other living beings; the vaiśyas especially protected the cows and produced enough food for the whole society, and the śūdras assisted the other classes with their work. Śāntanu was so powerful and so full of good qualities that all the other kings accepted him as the king of kings naturally.

After Śāntanu retired, Citrāṅgada took over his father's position. But his rule did not last long, for he was challenged to a contest by a gandharva of the same name. They fought each other for four years, and in the end the gandharva was victorious by his greater mystical powers over the most powerful kṣatriya on earth at that time. Thereafter, Bhīṣma had the still minor Vicitravīrya inaugurated as heir to the throne.

Bhīṣma robs the princesses of Kośala

A few years later, when the boy had grown into a handsome youth, the son of Gaṅgā personally took care of Vicitravīrya's marriage. When Bhīṣma learned that the three Apsara-like princesses of Kośala — Ambhā, Ambikā and Ambālikā — would choose their groom at a svayaṃvara,6 he decided to rob them for Vicitravīrya. At the svayaṃvara thousands of kṣatriyas kings had gathered. And even before all their names had been read out, Bhīṣma abducted the young princesses before the eyes of the powerful kṣatriyas. They pursued him and rained down their arrows on him, but they were no match for the master of weaponry. Finally they turned back, and Bhīṣma brought the beautiful king's daughters to Hastināpūra unhindered.

One of the princesses, Ambhā, did not agree to become Vicitravīrya's consort because she had already chosen her husband. She wanted to marry Śalya, the king of Madras. Bhīṣma therefore took her to Śalya, but he rejected Ambhā because she had already been touched by another (Bhīṣma). Ambhā then asked Bhīṣma to marry her. Bhīṣma, however, could not comply with her wish because he was bound by the vow of lifelong celibacy.

The princess was very disturbed by this and went into the forest. There she met Paraśurāma, who was Bhīṣma's teacher of arms. She complained to him and he promised to help her. Paraśurāma asked Bhīṣma to take Ambhā as his wife. Bhīṣma firmly refused. This made Paraśurāma so angry that he wanted to kill Bhīṣma. Śrī Paraśurāma is the warrior incarnation of the Supreme Lord who appeared to destroy the entire Kṣatriya race of the earth many times in succession because the kṣatriyas were abusing their power and misbehaving towards the brāhmaṇas. Bhīṣma and Paraśurāma fought each other for twenty-three days, but neither could defeat the other.

Ambhā then decided to undergo severe austerities in order to obtain Śiva's blessing to be able to kill Bhīṣma. When the mighty Śiva was satisfied with the performance of her strict asceticism, he granted her the boon to be the cause of Bhīṣma's death in her next life.

Vyāsadeva begets Pāṇḍu, Dhṛtarāṣṭra and Vidura

King Vicitravīrya is the example of a person who shortened his life through sexual overindulgence. He sported with his two wives for seven years and finally died of consumption.

To continue the Kuru dynasty, Vyāsadeva, the brother of Citrāṅgada and Vicitravīrya, begot a son with Ambikā at his mother's request. In Vedic culture, it was permissible for a man's brother to father a child with his brother's wife if the wife could not have a child by her husband. Vyāsadeva was an ascetic dressed in rags with matted hair. As he had taken a vow not to cleanse his body for a year, a strong unpleasant smell emanated from his body. When he approached Ambikā, she closed her eyes because she could not bear the sight of him. Because of that, her son Dhṛtarāṣṭra was born blind. Satyavatī asked Vyāsadeva to beget another son, this time with Ambālikā. Ambālikā turned pale when she saw the ascetic, and so her son was born with a pale skin and was named Pāṇḍu, „the pale-skinned one“. After that, Satyavatī asked the saint a third time to beget a son. She told Ambikā to receive the ṛṣi once more in her chamber. But the princess was so disgusted at the thought of uniting with the ugly dirty ascetic that she had a beautiful maid receive Vyāsa in her place. The maid behaved very reverently and devotedly towards the sage. From this union came Vidura, who later became world-famous for his wisdom and righteousness.

Yamarāja is cursed by the Ṛṣi Māṇḍavya

Vidura was a partial extension of Yamarāja, the wise judge of sinners. It had been Yama's desire to be allowed to participate in Kṛṣṇa's transcendental pastimes and by the merciful providence of the Supreme Lord, this wish was granted to him. Yamarāja had once inflicted an excessively severe punishment on the ṛṣi Māṇḍavya for a cruel act he had committed as a child, whereupon Māṇḍavya later cursed him to take birth on earth.

Vaiśampāyana told the following story in this context: „Māṇḍavya Ṛṣi, ever devoted to the practice of austere tapasya, had once taken a vow of silence. One day, as he stood — absorbed in meditation — with his arms raised like a pole in front of his hut, some robbers passed by, pursued by the king's police. They hid behind the ṛṣi's house. When the policemen came and asked the ṛṣi where the robbers had run to, he naturally gave no answer. The people finally found the robbers, and thinking that Māṇḍavya was in cahoots with them, they dragged him along with the thieves to the king's city. The thieves were impaled on wooden stakes, as was the innocent ṛṣi, who did not deviate from his vow and did nothing to escape punishment. The thieves eventually died, but the ṛṣi remained alive.

When some other ṛṣis learned of Māṇḍavyas pitiable condition, they went to him and comforted him and then went to the king. The king was very frightened when he heard that a brāhmaṇa had been impaled and went to him with the ṛṣis to fall down at his feet and ask for forgiveness. Māṇḍavya did not resent the king's punishment because he was aware that he had to endure these torments because of a past sinful act. The king's people tried to pull the pointed stake out of the sage's body, but they failed — the stake broke off and the tip was still stuck in his body.

After death, the sage's soul was elevated to a heavenly planet. One day he visited Yamarāja and asked him for what sin he had been punished so severely, and the Lord of Righteousness told him that once in his childhood he had impaled an insect on a straw. Because the ṛṣi thought this punishment unduly harsh, he cursed Yamarāja to take birth on earth.

Mahārāja Pāṇḍu kills Kindama and is cursed by him

When Pāṇḍu had grown into a youth, he was installed as Vicitravīrya's heir to the throne. He married two women, Pṛthā, also called Kuntī, who was the daughter of King Kuntibhoja, and Madrī, the daughter of the King of Madras. The blind Dhṛtarāṣṭra married Gāndhārī, the daughter of the king of Gandhāra, and Vidura obtained the daughter of king Devaka as his consort.

Soon after his marriage, King Pāṇḍu and his army subjugated the kings of the earth. Then he retired to the forest with his two wives, as he did not much care for the opulent palace life in Hastināpūra and he was also a passionate hunter.

One day, while hunting, he accidentally killed the ṛṣi Kindama. The ṛṣi and his wife had taken the form of a pair of deer, and were in the process of uniting sexually when Kindama was struck by Pāṇḍu's arrow.7 Before the ṛṣi died, he cursed Mahārāja Pāṇḍu to also die while he unites with his wife.

Notes

1 Nagas are powerful serpentine creatures that possess mystical powers and can take on different forms, for example. They exist mainly in regions below the earth.

2 Located about 200 km south of Delhi

3 Those who are personally killed by the Supreme Lord attain liberation. Such grace, however, is granted to only a few demons.

4 Not to be confused with King Rishabhadeva's son, who bore the same name.

5 "Someone who has dedicated his life to the Supreme Lord"

6 A ceremony in which a princess chooses a groom from among many suitors or many kṣatriyas compete for the hand of a princess.

7 They had taken the form of a hind and a stag to unite outside a time of copulation forbidden to civilised men.

Mahabharata - Jewel of the Poets is available as an ebook and also as PDF from Atmarama Verlag, Barnes & Noble, Google Play, Apple, Kobo and others.